A Break With Britishness

It was not until 1925, the year which saw the formation of the Welsh National Party, that a section of the Welsh Nonconformist petty-bourgeoisie abandoned the traditional British allegiance of its class. It is hardly surprising that the most prominent and influential members of this small group were intellectuals since it was only they, at that time, who were able to discern something more of the past of their nation than was revealed by the educational system of the conquering state. The growth of the party was slow, for the following reasons:

1. The thorough penetration of British imperialist ideology among the members of the

class to which they belonged.

2. Their inability to gain the support of industrial workers because of: (a) their cultural and academic conservatism and their attachment to the individualistic,puritanical, rural ethos of their class. (b) the influence of the Labour Movement, its Englishness and internationalism — sometimes honest, sometimes a front for Britishness — on the working class.

So Plaid Cymru started its political career as a reactionary party, albeit with a socialist fringe (mainly refugees from the disintegrating Independent Labour Party). As the British Empire dissolved in the post-war years and as England declined in importance in political and economic terms, there was a growth of national consciousness among the Welsh petty-bourgeoisie and the working-class.

This has been reflected in the growth of Plaid Cymru, now under the mellow and more populist leadership of Gwynfor Evans, and in the limited successes of Cymdeithas yr laith Gymraeg and other pressure groups.Yet the mass of the Welsh people have remained unmoved, if not untouched, by appeals to their Welsh nationality. Part of the explanation lies in the nature of the

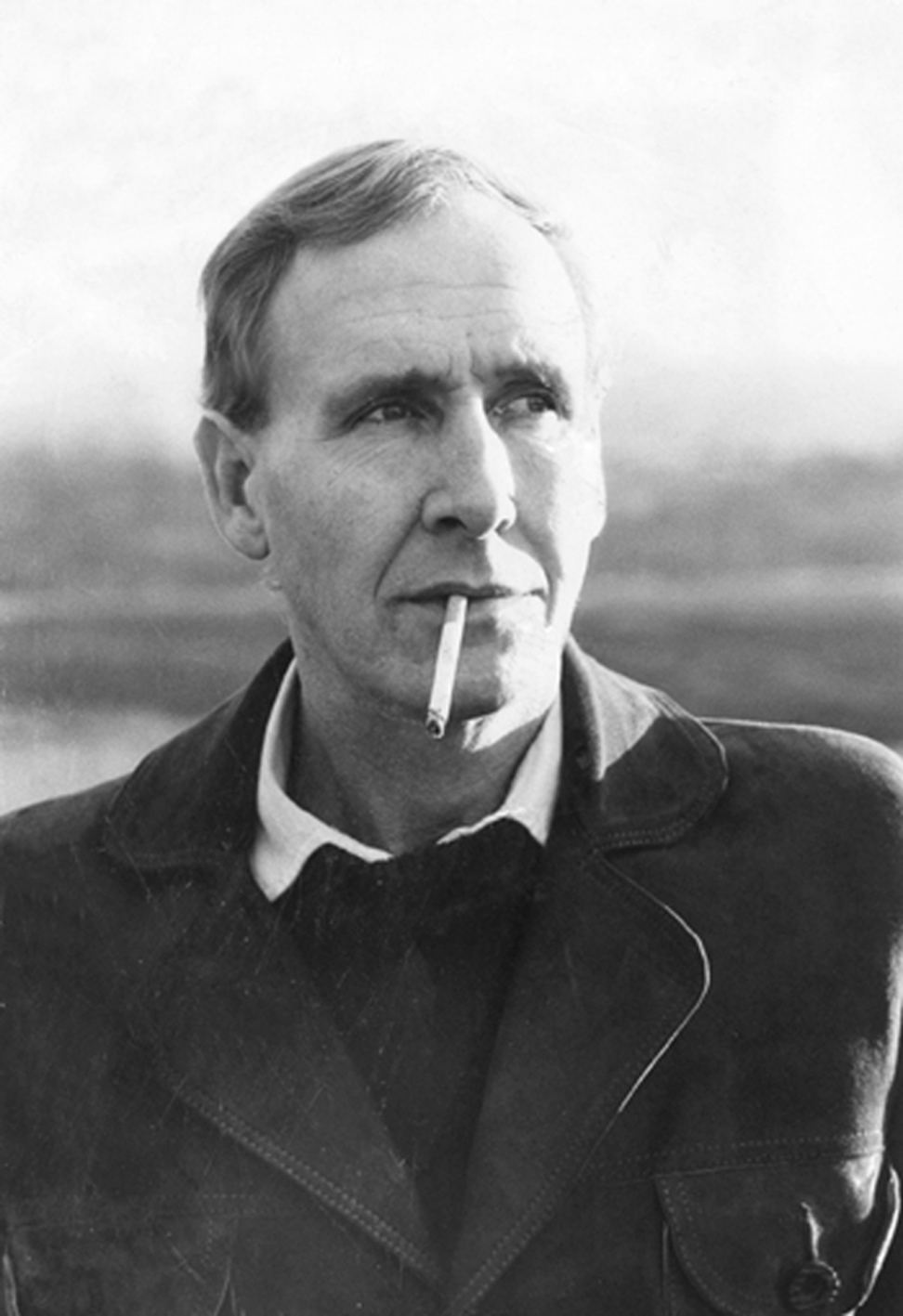

party’s appeal, itself derived from its leaders’ conceptions of “Nationalism”.In 1923 Saunders Lewis presented his Nationalism as follows:

“Another name for nationalism is conservatism. In essence, nationalism and conservatism are one and the same... Now, the national movement is a reaction — an attempt to nurture a Welsh conservative party, and to safeguard the civilization in

which we share.” (Y Faner, 6 September, 1923).

The terminology was unfortunate; and the obsession with conservatism, “standing still’, could hardly have appealed to a Welsh working class determined upon change. Singing the praises of “civilization” found little echo in mining valleys suffering the cruelties of capitalism.

Half a century later, Gwynfor Evans offers this ‘definition’:

“Nationalism varies so much from country to country that there are nearly as many nationalisms as there are nations, each one taking its character from the nation’s history and circumstances.” (Barn, August 1979).

We reject the “stagnation” definition of nationalism and the second, nebulous one. Both are uselessly abstract and ambiguous. For us, Nationalism is a philosophy fashioned by an economic class, using nationality to establish or maintain a State in pursuit of their own economic, political and social objectives. No Welsh State exists because no class has, in modern history, considered it essential to its class interests. Owain Glyndwr and his followers succeeded in setting up an independent Welsh State at the beginning of the 15th Century. It was short-lived: within years of that heroic venture the noblemen of Wales had struck upon a surer way of furthering their interests, namely by enlisting in the armies of the English King and dissolving themselves into the English aristocracy. This process received the royal seal of approval with the Acts of Incorporation under the Tudors, themselves of Welsh aristocratic descent.

By 1925 the political, social and economic aims of the Welsh petty bourgeoisie had, like the Welsh aristocracy before it, been largely fulfilled within a British framework. Hence Saunders Lewis and his companions could scorn “materialistic” Welsh Nationalism from their position of comparative, material comfort. No, the Welsh State they desired would perform a moral and sublimely civilized role: the aim was not independence, declared Saunders Lewis in his Principles of Nationalism, not even unconditional freedom, but just as much freedom as would be necessary to safeguard “Welsh Civilization’. And today, for many well-heeled Welsh Nationalist academics, broadcasters, littérateurs and clerics — “Cymry da” — their Welshness and command of the Welsh language is a decoration, worn on their sleeve to set them apart from and above the non-Welsh speaking “materialistic” herd; often Welshness is the vessel for their spiritual and religious values, supplying a meaning and source of daily anguish to there otherwise uninteresting lives. Of course, meeting the needs and aspirations of the common people, in Wales or England, is another matter entirely. This could not be done by the British State without transforming its very foundations — changing from a system based on exploitation and production for profit, to one producing for use in a people’s

commonwealth.

Even in its most harmonious and socially-accepted period, from 1945 to the mid 1960s, British Capitalism failed to eradicate unemployment or to satisfy the requirements of workers and their families in such areas as housing, education and social services. The prospects for the next quarter-century at least are no more favorable . History has proved and the future will confirm: unlike other classes, those who live by their labour alone have a vested interest in fundamental change, in building a Socialist society.Similarly in Wales, only the working class holds interests that are intrinsically in conflict with those defended by the British State. So the issue is whether the mass of the Welsh people should — or indeed, can — strive for economic, social and real cultural liberation on an exclusively British/European/global scale, or whether they should add another dimension to one or more of these: the drive for a Welsh Republic. The case for opening up and concentrating upon this front is, we hope, proposed in the remainder of this pamphlet. But where we must start is with the political consciousness of the Welsh working class, past and present.

Comments

Post a Comment